The insights from sociocracy don’t only apply to formal organizational governance. Wherever people make decisions together – or by themselves – the clarity of process that we learn in organizational governance is beneficial to every-day situations.

This also applies the other way: what we are seeking to make habits when learning sociocracy can be practiced in every-day situations. You don’t have to be the facilitator of a sociocratic circle to practice sociocratic meeting facilitation – practice on your children or you friends instead!

When giving examples to students of sociocracy, I often find myself giving examples from every-day life because it’s so relatable. The feedback I get is that people realize that the biggest opportunity for change might actually be in those very moments. That’s what I am referring to as “everyday sociocracy“.

Among all the different lessons from sociocracy I am choosing four to talk about here. Their biggest contribution is the clarity and intentionality they bring to any situation.

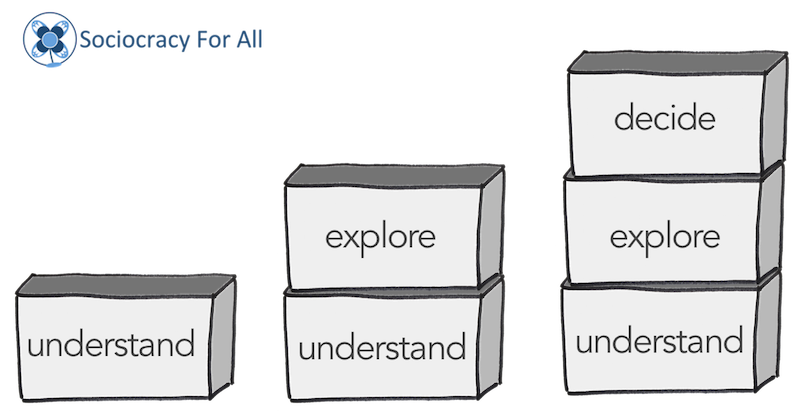

Context: understand – explore – decide

Evolving from sociocratic tradition, we use a three-step decision-making process in our handbook Many Voices One Song. Each group process consists of up to those three phases. Each of those will be relevant in everyday sociocracy.

Understand: make sure there is an understanding of what the other person is bringing (it might be a report, just an idea or a proposal). If there is something you don’t fully understand, ask clarifying questions until you do.

Explore: what comes up in you in reaction to the piece the other person is bringing? Do you have ideas, reflections, reservations?

Decide: in this phase, we are making a decision. In sociocracy, this means we are checking whether our proposal creates harm anywhere. If not, it is probably safe to go ahead and try it out.

A significant aspect of consent decision making is that it is explicit: it is clear what the proposal is and that this is a moment of a decision.

Clarity: Am I seeking to understand or am I giving opinions?

This section is about clarity on the distinction between the understand phase and the explore phase. A reaction or opinion is very different from a clarifying question.

In the understand phase, our attention is on the other person, trying to wrap our head around what the other person is saying, proposing, experiencing.

A friend in Sociocracy For All told me the story of how his marriage of 40+ years changed when they both realized how often they reacted to what they thought the other said instead of listening to what the other was really saying. He said it improved their relationship to have that clarity.

By the way, there is no 1:1 fit with the format of the sentence here. A clarification can end on a period (‘I don’t understand whether you’re talking about the morning or the afternoon of that day’) and a reaction can look like a question, for example in, “don’t you think going out on a school night two days in a row is way too much?”

For a while, when I was new to this and fascinated by it, I made it a habit to never give opinions unless I was explicitly asked for one. It’s an enlightening experiment to do. Really, my humbling insight was that not much is lost when we don’t give opinions. Instead, we get to focus more on the insights and perspectives the other person might be bringing us. Much more fun!

Clarity: Am I asking for feedback or are we making a decision?

The next difference is between phase 2 and 3, between exploring reactions and making decisions. In every-day situations, they often blend in with each other, and it’s a problem. Here is an example. Let say my partner and I are talking informally about the weekend. He says, he saw a theater performance coming up on Saturday at the library, and he was wondering whether the younger kids would like it. I say, yeah probably, if it’s not too scary of a story for the 9-year-old because she doesn’t like scary costumes. So we talk about that for a bit and then we get interrupted. The question of the day is: did we just make a decision to go see the theater performance on Saturday? The reality is, it’s unclear. And the reality is that I can’t even count the times in my parenting life unclear communication of that pattern created a problem.

Decision making is a magic thing – we say that something is now decided and then it is decided. We can make things so just by saying the words. But for the magic to work we have to be clear that this is the moment of decision making. We have to be clear whether we’re just exploring options and giving reactions (explore phase) or whether we’re consenting to a plan.

Sometimes the lack of clarity gets to me and I use the word “hereby” because “hereby” is a magic word. (For example, it’s used in what linguists call performative speech acts like ‘I hereby name you Eve‘ or ‘I hereby declare you husband and husband‘). In those moments when I want to be explicit, I’ll say things like, ‘ok, just to be clear after all this back and forth: I am hereby asking you whether you agree to trade childcare weekends with me. Let me know by tonight because I need to book a plane ticket.” Yes, it can sound funny but it’s crystal clear!

A less formulaic way to do it is to say ‘hey, can I just check whether it’s ok to…“, or “I need to decide on my weekend. Let’s decide now whether we’re going to the movies on Friday or on Saturday.”

Knowing how to make a proposal when it’s time to make a proposal is liberating. You leave behind the noncommittal bouncing of ideas and get to move to the actionable phase. It’s powerful.

But even more: if you explicitly ask for consent by making a clear proposal, you are giving the other person an opportunity to object. The power of consent – not only sexual consent but any consent – is in having being asked transparently which is a first precondition to being able to say no. I personally think we need to ask more often, and ask more explicitly, inside and outside of organizations. Being clear about that and about the difference between exploring ideas and asking for consent on a concrete plan is a first step.

Clarity: who is a decision maker here?

When an individual or a group is moving towards a decision, people have all kinds of reactions. For example, I might be talking with a friend about how I really want to take on a job at my local volunteer organization. My friend is convinced that it’s not a good idea and tries to talk me out of it. Even considering her feedback, I end up signing up for my own reasons. Days later, I talk with my friend again and she is upset that I did ‘although we said that I wouldn’t’.

Firstly, who is a decision maker? We weren’t making a decision but just talking about our reactions. (That’s what we talked about in section two.) We couldn’t possibly make a decision together because that decision is most likely not in our domain. My friend is not a decision maker on my volunteer commitments. My kids are not decision makers on what I make for dinner (unless there is a family decision about that). My neighbor is not a decision maker on how often I mow the lawn (unless there is an agreement about that that we’re both committed to). I might have opinions whether my teenager should do their homework or skip it but I am not a decision maker. On the other hand, if I have to sign off that my 3rd grader completed her 45min of reading time, then I am a decision maker on whether it counts if you read but spend more time arguing with your sister. (The ever-changing nature of who gets to decide what is one of the things that make parenting so tricky!)

It’s incredibly liberating to have clarity on who is a decision maker where. Firstly, you know who needs to be asked. And secondly, you know that all opinions from non-decision makers are just that: opinions. You can consider them, but they are not binding. Instead of reacting to them you can take them as useful information.

Clarity: what’s a negative reaction, what’s an objection?

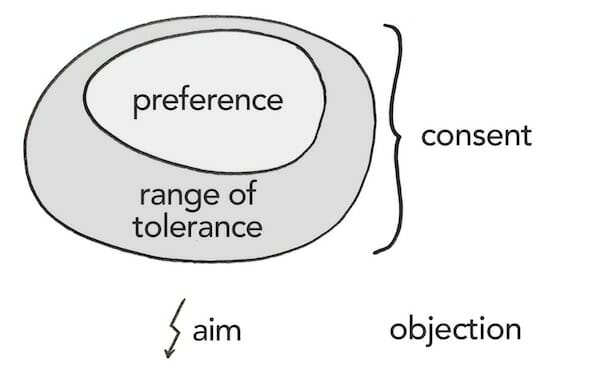

If someone is a decision-maker and they don’t like an idea then there needs to be clarity on whether they have negative reactions or whether they object.

For example, back to my example of the theater performance at the library. Let’s say it was clear that my partner was suggesting we go. When I say ‘I am wondering about it being too scary for Julia‘, am I just wondering out loud, or am I objecting to the proposal? That’s a big difference! And it’s important to be on the same page on that. For example, my partner might hear that and conclude that he is going to make sure to sit right next to her to make sure she is fine. She might still be scared and come home in tears and I might say “what, you took them anyway although I said no, it would be too scary?” You get the idea. People end up in situations like that all the time because we’re not clear. Let’s say I just started an exercise routine and want to make sure to eat a lot of protein. My partner might suggest we eat pasta because he is in a rush and really wants to eat together with me before he leaves. When I say, ‘well, pasta is not exactly high in protein‘, did I just object, or did I just comment saying that it’s not perfect?

In my quest for more clarity, when someone makes a comment like that, I will sometimes ask explicitly ask, ‘ok, I hear you on it not being your first choice – but can you live with it for today?’ Really, that’s just an informal way of asking, is this just not your preference, or is it outside of your range of tolerance? I find that we often get so caught up in our reactions that we don’t even know. If we’re more honest with ourselves, about that difference, we can let go of more imperfections. If we’re more clear with others about our own objections (or lack thereof), then we can empower them to hear and consider our feedback and still make their own decisions. If we don’t shoot down ideas just because they are not perfect, it will be more likely that we’re heard when we actually have a reason to object.

Clarity wins!

As for me, in some moments, I prefer clarity over vagueness. Clarity about these concepts and in our communication helps us have clear boundaries for ourselves and others. We can be more open to feedback because we know how to take it. Instead of spinning in the idea stage, proposals help groups to kick into action. Explicit decision making empowers ourselves and others to say yes or to object. In my view, clarity wins every time.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.